It can be hard enough to pin down exactly why so many people like cars. Many gallons of ink and billions of ones and zeros have been expended by people much cleverer than myself trying to nail down why you can take some rubber, metal ore and plastics and make a washing machine from them and no one will care while if you use to make a car some people will care about it so much that they’ll spend their own money to create some space on the internet where they will talk about it every Friday evening.

If the specific appeal of cars as a whole rather defies explanation what about particular bits of cars? As far as I know there are no enthusiasts clubs for the Saab Inca alloy wheel or the Ford Cortina ‘peace symbol’ rear light, as iconic as they may be. Some Land Rover enthusiasts may look upon the leaf spring as an existential symbol but even they don’t covet the springs themselves (at least, I hope they don’t…).

That would make this sort of thing very dubious.

That would make this sort of thing very dubious.

Of course lights, wheels and springs are rather dull. Engines are more exciting because they make nice noises and within their dull metal exterior lurks a certain magic that takes a strange smelly liquid and turns it into rotational power. But even then it’s all about what the engine can do when placed in the front (or back, I suppose) of a car and put to work. In and of itself an engine, even an excellent one, is useless and not worthy of any regard as an object.

With the exception of a V8.

Why does this particular, and not especially interesting, engine layout garner such passion amongst enthusiasts of things mechanical? People will make owning a V8-powered car a life goal while others will expend hours of creative engineering effort to put V8s where they shouldn’t be. The V8 has been immortalised on film, in music, in artwork and in marketing. Crowds of people will gather to listen to a V8 engine running and even non-car people will make appreciative noises.

Of course there have been plenty of other engines that, individually, have gained their own cultural place (the flat air-cooled VW and Porsche engines spring to mind) but they’re specific makes and models of engines. All V8s of any make, age, size, type and use seem to collect this near-reverential appeal.

Let’s start with the obvious thing, the first answer that anyone will give if you ask them what the appeal of a V8 engine is- the noise (or ‘the soundtrack’ as unimaginative writers have called it for decades). No engine makes quite the sound of a V8. The basso-profundo burble of a big-capacity V8 exhaling through a low-restriction tailpipe is the sort of thing that does, literally, make your spine tingle.

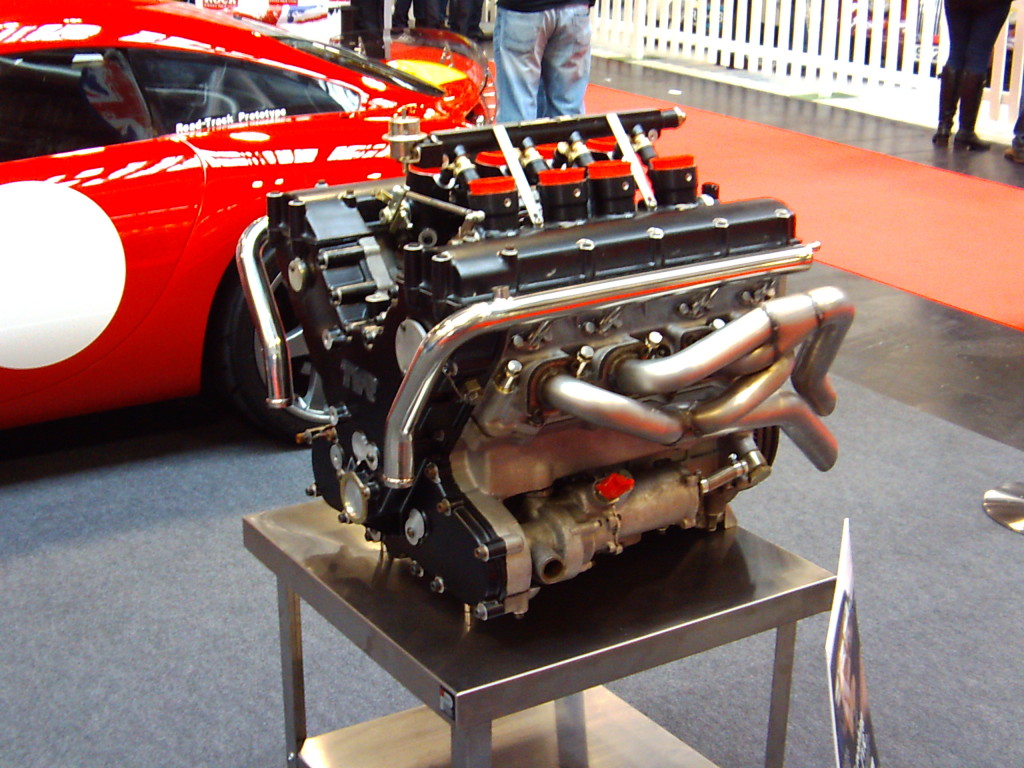

Now, just as the purpose of musical theory is to deconstruct the most beautiful, emotional experiences into bland sequences of black dots and lines on a stave I can say that the ‘magic’ of the V8 sound is no great mystery. A cross-plane V8 engine (where the crank throws of each cylinder are set at 90 degrees to each other) has a firing order which irregularly switches between the left and right banks of cylinders so you get pulses of exhaust travelling down the pipe. The principle is just like a big 16-foot organ pipe with a reed setting up standing pressure waves and the effect is the same- a rhythmic, low-frequency pulsing noise that is naturally harmonic and can be easily made even more effective by some careful tuning on the part of the manufacturer. Incidentally V8s with flat-plane cranks, as favoured in racing, don’t do the same trick which is why they either sound very bland (the criticism levelled at the McLaren MP4-12C) or they scream instead of bellow (like all Ferrari V8s). Even with cross-plane engines its having two groups of four cylinders that produces the effect because it’s just enough to set up the pulsing effect without losing the ‘beat’ in between gaps in the firing sequence while being not enough to make them all blend into one another.

Now, just as the purpose of musical theory is to deconstruct the most beautiful, emotional experiences into bland sequences of black dots and lines on a stave I can say that the ‘magic’ of the V8 sound is no great mystery. A cross-plane V8 engine (where the crank throws of each cylinder are set at 90 degrees to each other) has a firing order which irregularly switches between the left and right banks of cylinders so you get pulses of exhaust travelling down the pipe. The principle is just like a big 16-foot organ pipe with a reed setting up standing pressure waves and the effect is the same- a rhythmic, low-frequency pulsing noise that is naturally harmonic and can be easily made even more effective by some careful tuning on the part of the manufacturer. Incidentally V8s with flat-plane cranks, as favoured in racing, don’t do the same trick which is why they either sound very bland (the criticism levelled at the McLaren MP4-12C) or they scream instead of bellow (like all Ferrari V8s). Even with cross-plane engines its having two groups of four cylinders that produces the effect because it’s just enough to set up the pulsing effect without losing the ‘beat’ in between gaps in the firing sequence while being not enough to make them all blend into one another.

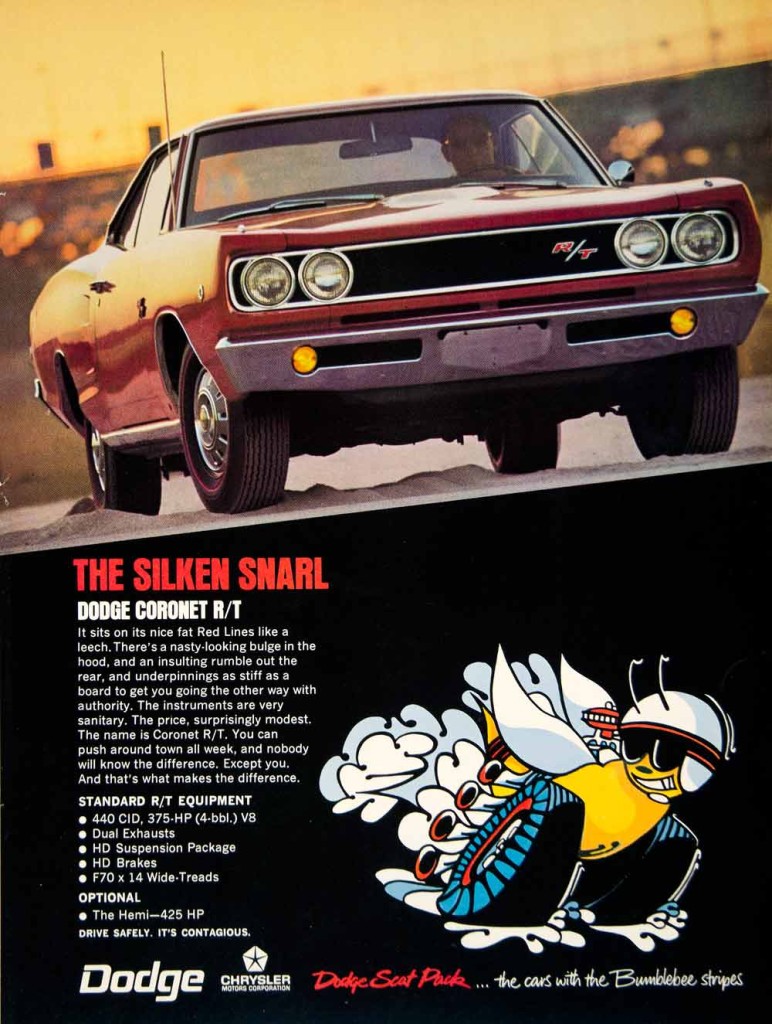

As you’d expect Detroit’s marketing men had it sussed ages ago.

So that’s the magic-ruining science, but that doesn’t explain the appeal, just as Phrygian modes, interrupted progressions and subdominant textures aren’t why people go all misty-eyed whenever they hear ‘Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis’. To keep asking the question- what’s the actual appeal? Why does the trailer for Jack Reacher feature an idling V8 under all the rest of the action? It’s not even a proper car film. Can you imagine that trailer playing out to the top-end clatter of a Simca 4-pot or the turbine hum of a BMW straight-6? No. So why the V8?

I think it’s something to do with the animalistic nature. Think of the clichés used to describe the noises a V8 makes, most of which I’ve already used- ‘burble’, ‘bellow’, ‘roar’, ‘snort’, ‘snarl’. These are organic, predatory noises. Listen to that Chevelle’s big block V8 in the film trailer. At idle it has such an irregular beat that it sounds on the verge of cutting out. It’s an unpredictable noise suggestive of great power and force. Given its head (more animal terminology!) a V8 offers a symphony of a thrashing exhaust, induction roar and the sound of eight fuel/air charges igniting in perfect sequence. Just as perfection is boring the slightly ‘rough’, uneven quality is what gives the engines its appeal over any other engine of the same capacity and power but a different configuration.

So that’s the noise dealt with. There are other, more prosaic factors at work, like the smoothness of the delivery or the V8s extraordinary mechanical refinement due to all its working parts balancing out each other’s movements. It shouldn’t be forgotten that the V8 is a rather schizophrenic engine. It can be about noise, showing off and power or it can be about utter refinement and ease of travel. It was actually invented for the latter reason- Cadillac and Rolls-Royce championed the V8 because of its luxurious nature rather than its animalistic noises. But this isn’t exclusive to the V8. A straight-6, a V12, a straight-8 or even a little flat-2 can offer similarly top-rank refinement levels in the right application.

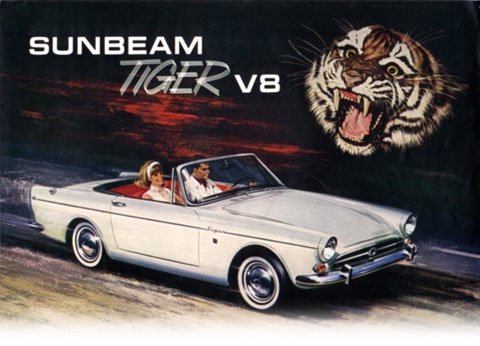

I think the V8s appeal is really more sociological. It is something to be aspired to but it is very attainable. It’s not like that other desirable icon of internal combustion, the V12, which is only found in ultra-expensive exotica. Because of their powerful yet compact nature V8s can be a practical choice as well as a lifestyle statement. Take the ex-Buick Rover V8, probably one of the most famous engines in the world. As well as lurking under the bonnet of Range Rovers and Prime Ministerial P5Bs it has been found in the MGB , the Sherpa van, the Land Rover, low-cost sports cars like Ginettas and Westfields. The Sunbeam Tiger was hardly cheap but neither was it entirely unaffordable.

Again, this can be put down to boring economic reasons (it’s relatively easy to drop a V8 into a car designed for a straight-4. Much easier than dropping in, say, a straight-6 *cough*MGC*cough*) but that’s the crux of it. The V8 is an attainable luxury. It’s unusual enough to be special but common enough so that it’s affordable. You can buy a V8-engined Land Rover for a couple of grand. If you must buy new then Vauxhall will sell you over 6 litres of 8-cylinder goodness and you’ll have change from £40k.

Again, this can be put down to boring economic reasons (it’s relatively easy to drop a V8 into a car designed for a straight-4. Much easier than dropping in, say, a straight-6 *cough*MGC*cough*) but that’s the crux of it. The V8 is an attainable luxury. It’s unusual enough to be special but common enough so that it’s affordable. You can buy a V8-engined Land Rover for a couple of grand. If you must buy new then Vauxhall will sell you over 6 litres of 8-cylinder goodness and you’ll have change from £40k.

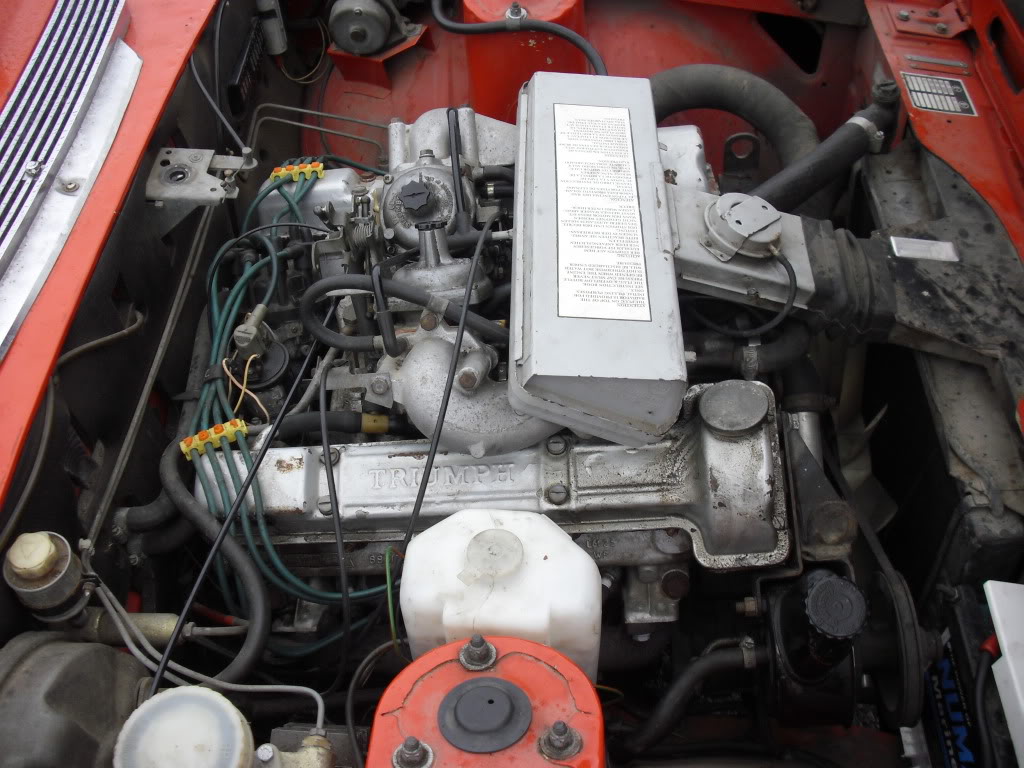

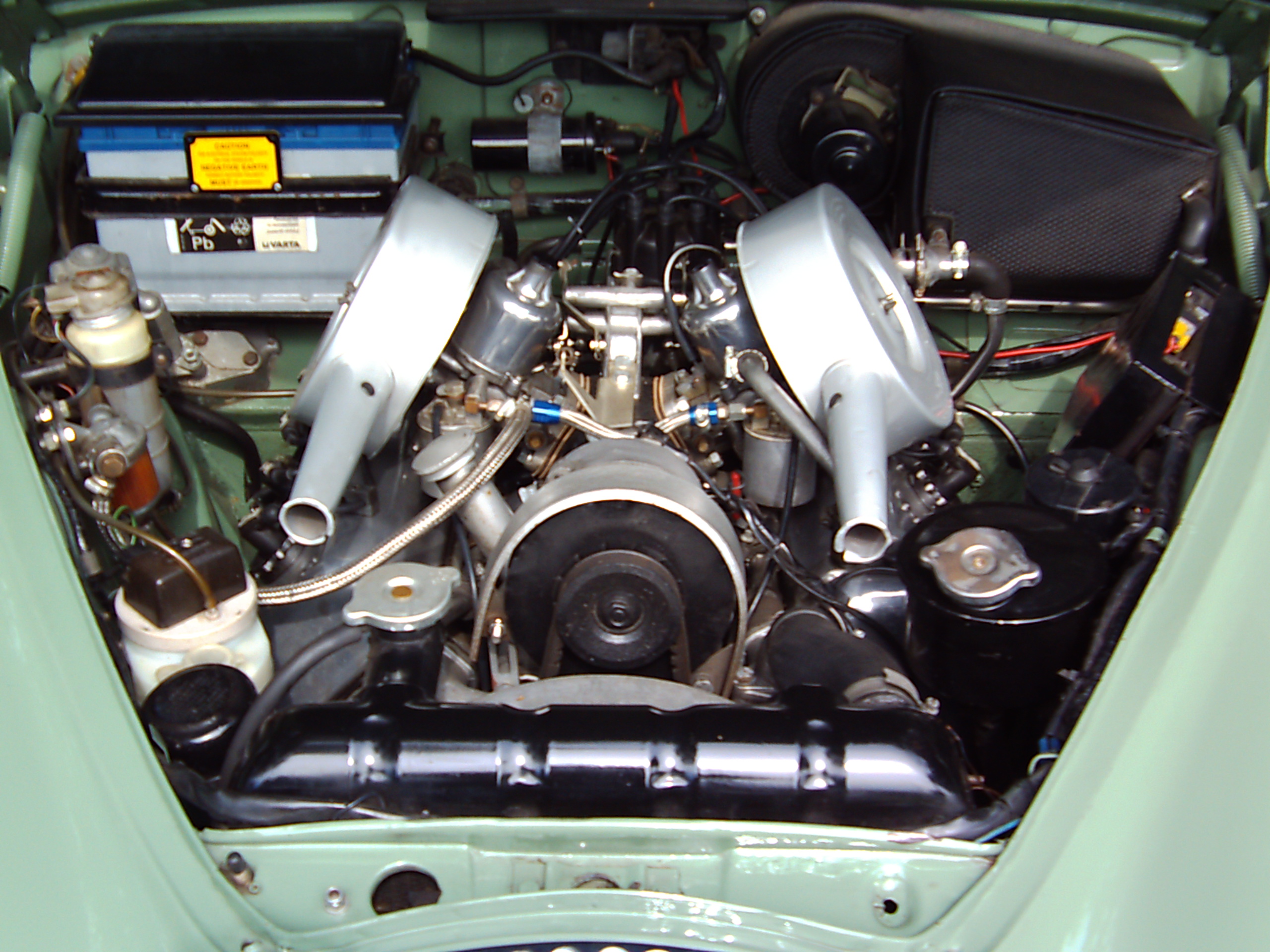

Personally I think there may be something in the look of a V8 as well. It must be down to the basic symmetry and that’s why people will pay four-figure sums to have a coffee table built from a slab of glass screwed to a polished V8 block. One of my personal best looking engines is the Daimler 2.5 V8, with its pleasingly clean rocker covers and spark plug holders, centrally-mounted dynamo and air cleaners that look like the gun turrets of battlecruiser.

Really, I suppose, the reason why we all love the V8 is because it embodies the very thing I mentioned in the first paragraph- the way that an inanimate object can become something strangely desirable and symbolic of something much more than the sum of its parts and materials.

Really, I suppose, the reason why we all love the V8 is because it embodies the very thing I mentioned in the first paragraph- the way that an inanimate object can become something strangely desirable and symbolic of something much more than the sum of its parts and materials.