Today brought sad news for all followers of British Leyland and its products, with the announcement of the death of Dr. Alex Moulton. Dr. Moulton passed away yesterday at his home in Bradford-on-Avon at the age of 92.

Dr. Moulton was, of course, the suspension engineer who worked with his close friend Alec Issigonis on all of the latter’s iconic car designs, of which the first and most iconic was the Mini. Moulton’s speciality was suspension and his system of rubber cones (in its own way just as innovative as Issigonis’ brainwave about transverse engines and gearboxes in the sump) was key to the success of the little car, helping produce the two big Mini clichés- the ‘Tardis-like’ interior and the ‘go-kart like’ handling.

Moulton’s association with Issigonis went back to before the Mini, having manufactured rubber springs for an Austin Seven-based racing special that Issigonis had created before the War. Moulton had then worked with BMC to produce the ‘Flexitor’ suspension system of trailing arms and rubber torsion units for the Austin Gipsy 4×4.

Moulton’s choice of rubber as a springing medium stemmed from his background- his family had been one of the pioneers of the modern rubber industry in the 1860s with C.S. Moulton & Co. battling it out with the better-known Avon Rubber Co. The Moulton family firm carved out a niche making buffers and rubber suspension parts for railway wagons, inspiring Alex Moulton to apply the same principles to cars. By the time the Mini was in development Moulton had sold his firm to Avon to fund the creation of his own company, Moulton Developments, to design and market his ideas for car suspension systems.

Moulton always took an unconventional approach (one of the reasons he worked so well with Issigonis) and was very much an ‘engineer’s engineer’, favouring the best solutions and products from an engineering perspective rather than the needs of marketing or accountants. He had a habitual dislike of complexity. Whilst very impressed with the ride comfort and handling of the Citroen 2CV he objected to the expensive, maintenance-heavy and complicated mechanical suspension system and developed his Hydrolastic system to work on the same principles with no maintenance requirements and only four moving parts.

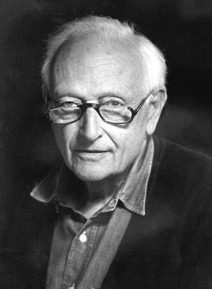

Alex Moulton (left) and Alec Issigonis (centre) with a diagram of a Hydrolastic displacer unit.

Alex Moulton (left) and Alec Issigonis (centre) with a diagram of a Hydrolastic displacer unit.

Hydrolastic-equipped cars (such as the BMC 1100/1300 and 1800/2200), thanks to their fore/aft interconnection and fluid damping, offered vastly superior ride comfort to anything else of their size whilst the independent motion, short travel and progressive springing provided by the rubber cones also provided very secure and sharp handling. As with his work on the Mini, Moulton’s Hydrolastic suspension was key to the success of the 1100/1300 which was for many years in the mid/late ‘Sixties Britain’s best selling car model. The system was also fitted to Issigonis’ ‘big car’ projects, the 1800/2200 and the Maxi. Both cars proved surprisingly effective rally weapons due to the simplicity and reliability of the Hydrolastic suspension and the good ride greatly reduce the strain on the cars and crews. By 1970 (if my figures are right) around 25% of all the cars sold in the UK had some form of Moulton suspension system.

Hydrolastic was developed into Hydragas, working on the same principles but with pressurised nitrogen spheres acting as the springs rather than rubber (although rubber was still key to the design, which incorporated several rubber diaphragms and flapper valves). Hydragas further improved the ride quality of cars but the body control and handling was much more controversial due to the increased roll and float that the low-friction gas springs produced.

The unconventional nature of Hydragas played a big part in the poor reputation of the Austin Allegro, in which it made its debut but the system itself worked very well as an exercise in suspension engineering- typical of Moulton’s (and British Leyland’s) approach at the time. In fact the ever-growing problems at BL and the declining reputation of its cars unfairly tarred Moulton’s products with the same brush. In fact Moulton’s long-term development plans and his ruthless elimination of unneccesary components meant that his suspension systems were amongst the most reliable parts of any British Leyland car of the period.

Moulton and BL kept refining Hydragas to suit it better to market tastes and the system was key to the success of the Metro supermini and the MGF roadster, which became the last car to use a Moulton-developed suspension system when it ceased production in 2002.

Moulton’s name was featured prominently on the original version of his Hydragas suspension system.

By this time Moulton himself acknowledged that modern technology had made it possible to make conventional steel springs and hydraulic dampers that performed as well as, if not better, than his own systems and that the Hydragas units were now increasingly expensive to make. None the less he continued to actively develop and expand his ideas producing, amongst other products, ‘Smootharide’ cone springs for Minis which took advantage of the advances in rubber technology to improve the ride comfort of a ‘dry cone’ Mini to the point where it surpassed the original Hydrolastic system.

Dr. Moulton took a keen interest in the classic car scene as it developed and always expressed great pleasure in seeing people enjoy and care for ‘his’ cars. He remained close friends with Sir Alec Issigonis (despite his contribution to British industry in several fields Moulton was never knighted…) until the latter’s death in 1988 and staunchly defended his friend and colleague’s approach to car design.

He regularly welcomed classic car clubs and owners to his home in Bradford-on-Avon and was happy to show them his workshop, original drawings. He maintained an extensive personal car collection, including many used for the development of his suspension designs and ones that he had adapted for his personal use, such as late Mini Cooper fitted with Hydragas. As you would expect from a suspension engineer, Dr. Moulton also owned several Citroens and his main transport for many years was a V6 Citroen XM.

Moulton was always ready to talk about his work and personally corresponded with car owners from around the world if they had questions about his systems and, especially in more recent years, how to keep them on the road. He continued to refine his designs on paper and apparently was keen for Moulton Developments to restart production of replacement parts for Hydrolastic/Hydragas cars following the ceasation of mainstream production.

The good Doctor was also a keen lecturer and speaker, continuing to give talks at universities and societies until very recently. He also founded and managed the Alex Moulton Foundation, a charity to promote engineering at Further Education level.

Whilst proud of his work on automotive suspension, Moulton himself thought most highly of his Moulton Bicycle, which he developed in 1962 to redesign the bicycle from first principles. The Moulton Bicycle Company is still going strong today and, amongst many other features, their products use miniaturised Hydrolastic and Flexitor suspension units.

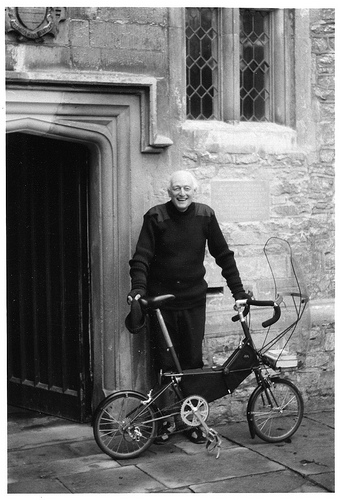

The good Doctor with a prototype Moulton bicycle, complete with front fairing and rear Hydrolastic suspension.

I deeply regret that I will now never get the chance to meet Dr. Moulton in person. As it is I can only form an impression from second hand experiences but they have only ever been of a true gentleman who was enthusiastic about his work yet humble about his achievements. His dedication to regularly meeting his ‘fans’, even if it was just an informal group of enthusiasts from an internet forum, speaks volumes, as does his dedication to answering their questions about his products.

Fortunately he was well aware of the number of people dedicated to keeping the cars he helped create up and running for as long as possible and I think doing that is the best possible tribute to a great man.