This blog was originally going to be along the lines of ‘old versus new’, until it occurred to me that even the ‘new’ component is now 22 years old and is closer to the year the ‘old’ one was built than it is to the present day. So instead we have a face-off between Old and Older.

It seems almost redundant to pit two Land Rovers against each other, regardless of the age gap between them. Lore states that as vacuum tubes gave way to transistors and microchips, tie-dye gave way to flares and shoulder-pads, and rock and roll gave way to punk and techno the Land Rover has been an ever-present unchanging facet of life. Reviews and magazines drop in lines like “unchanged in over 60 years” and “design icon”. Land Rover themselves see so little difference that they backdate the existence of the current Defender brand to 1948 whenever they get the chance. But can a vehicle really stay so unchanged for so many decades? Have all those engineers and designers up at Solihull just twiddling their thumbs and occasionally sketching new sidestripe patterns? These are questions that need to answered.

The two Land Rovers in question aren’t exact counterparts. One in a 1970 Series IIA 88-inch and the other is a 1990 Ninety County Station Wagon. The former is straight out of Emmerdale whilst the latter is more To The Manor Born. What they do have in common is that they are still in entirely original factory specification, which is a rarity in the world of Land Rovers.

Series IIA- The Sounds (and Smells) of the Sixties

This late IIA represents something of cross-over period for the Land Rover. Most noticeably it has its headlights in the wings rather than the inset grille panel. This change was required by lighting regulations in several countries (notably the USA and Germany) and, according to people with extravagant beards and tattered Barbours this was the beginning of the end for the ‘proper Land Rover’. There are other hints of the modern world- although this particular one still powers its minimal electrics with a dynamo an alternator was optional so it has a negative-earth system, bringing the British motor industry kicking and screaming into line with the rest of the world. In retrospect this Land Rover is also notable for being one of the last true Land Rovers. It was built by a still-independent Rover Company but in a few short years Rover would find itself part of British Leyland.

This late IIA represents something of cross-over period for the Land Rover. Most noticeably it has its headlights in the wings rather than the inset grille panel. This change was required by lighting regulations in several countries (notably the USA and Germany) and, according to people with extravagant beards and tattered Barbours this was the beginning of the end for the ‘proper Land Rover’. There are other hints of the modern world- although this particular one still powers its minimal electrics with a dynamo an alternator was optional so it has a negative-earth system, bringing the British motor industry kicking and screaming into line with the rest of the world. In retrospect this Land Rover is also notable for being one of the last true Land Rovers. It was built by a still-independent Rover Company but in a few short years Rover would find itself part of British Leyland.

These little details aside this Land Rover is still entirely representative of the Series II Land Rover launched way back in 1958 which saw many of the flaws and bugs of the earlier Series I models (only ever intended to be a quick post-war stopgap) ironed out. The Series II also had some basic styling elements courtesy of the masterful David Bache whose portfolio also included the Rover P6 and SD1. The short-wheelbase Series II is a likeable, almost cuddly vehicle, with its strange but satisfying combination of flat panels and curved edges, big goggly headlamps and proportions that are almost as wide as it is long.

For all the refinements that the Series II brought, and the few which had been added by the time this IIA was built, the Land Rover of the time was still a functional vehicle to an almost punishing degree. This one has a few optional extras chucked at it but when I reveal that these include (apparently) DeLuxe seats, an electric windscreen washer pump and a heater you’ll see that we’re still dealing with monastic comfort levels. The instruments are mounted centrally and consist of a speedo (reading up to a breakneck 70 MPH) and a multi-gauge containing fuel and temperature readouts. The few electrical switches look like something out of a Vulcan bomber and the stark labels and untrimmed metal panelling painted a dark green contribute to the military feel. Comfort isn’t a word usually associated with old Land Rovers and in this one the only soft furnishings are the seats. Everything else – dashboard, floors, bulkhead, transmission tunnel – is simply steel or aluminium sheeting.

The seats don’t adjust in any direction but the ‘one size fits all’ seating position is actually quite good. It’s a very upright posture, which adds to the apparent height of the vehicle and helps you easily see over the spare wheel mounted on the bonnet (although at 6′ 2″ I may not be the best to talk about that aspect). The DeLuxe seats are much better than the basic slabs of vinyl and are actually shaped to accept the human body which makes things much more bareable. Ventilation is courtesy of the famous flaps under the windscreen and the side windows which have a single half-length sliding panel which doesn’t open quite enough to comfortably get your head through.

The seats don’t adjust in any direction but the ‘one size fits all’ seating position is actually quite good. It’s a very upright posture, which adds to the apparent height of the vehicle and helps you easily see over the spare wheel mounted on the bonnet (although at 6′ 2″ I may not be the best to talk about that aspect). The DeLuxe seats are much better than the basic slabs of vinyl and are actually shaped to accept the human body which makes things much more bareable. Ventilation is courtesy of the famous flaps under the windscreen and the side windows which have a single half-length sliding panel which doesn’t open quite enough to comfortably get your head through.

Start-up is the usual procedure for a petrol Land Rover – full choke, turn the key, engine fires quickly, push the choke back in. The 2.25-litre petrol engine powered three generations of Land Rover and is renowned for its durability and simplicity. What’s often overlooked is its refinement. At idle the engine is virtually silent, with just a steady hum from the fanbelt and a gentle tick/tock from the distributor. Unfortunately the engine is encased in a 10-foot long biscuit tin and so all those noises and any vibration is amplified and transmitted throughout the entire vehicle which rather destroys the magic.

Start-up is the usual procedure for a petrol Land Rover – full choke, turn the key, engine fires quickly, push the choke back in. The 2.25-litre petrol engine powered three generations of Land Rover and is renowned for its durability and simplicity. What’s often overlooked is its refinement. At idle the engine is virtually silent, with just a steady hum from the fanbelt and a gentle tick/tock from the distributor. Unfortunately the engine is encased in a 10-foot long biscuit tin and so all those noises and any vibration is amplified and transmitted throughout the entire vehicle which rather destroys the magic.

The clutch is insanely heavy and the 4-speed gearbox is not slick. The box is a 4-speed with synchro only on 3rd and 4th. It is mated to a gear driven two-speed transfer box which drives the two live axles via propshafts. That’s a lot of gear-on-gear interfaces and they all make their presence felt as you drive. A lot of the gears are straight cut as well so you get a building whine from the drivetrain under power, a symphony of clonks and thuds as you come off the power and the forces in the system reverse and then a differently pitched howl from the cogs on the overrun. This is very helpful in judging downchanges into the lower regions of the box which need double-declutching and a technique approaching the karate-chop to engage, once the gear has been located on the very wide throw.

Performance is a mixed bag. The gearing is all quite low and closely spaced and with around 70 horsepower on tap in a relatively light, simple vehicle initial progress is quite brisk. The engine is also brilliantly torquey and you quickly realise that the best technique is to get into 4th gear as quickly as possible. This allows the IIA to happily pull at speeds at low as 20 MPH all the way up to the apparent top speed at a little over 60. At this velocity the wing mirrors start flapping around uncontrollably, the gearbox is screaming its protests and a general smell of hot oil suggests you slow down. At 50 or 55 the Land Rover is still in its comfort zone and will cruise with throttle travel to spare for mild inclines.

Performance is a mixed bag. The gearing is all quite low and closely spaced and with around 70 horsepower on tap in a relatively light, simple vehicle initial progress is quite brisk. The engine is also brilliantly torquey and you quickly realise that the best technique is to get into 4th gear as quickly as possible. This allows the IIA to happily pull at speeds at low as 20 MPH all the way up to the apparent top speed at a little over 60. At this velocity the wing mirrors start flapping around uncontrollably, the gearbox is screaming its protests and a general smell of hot oil suggests you slow down. At 50 or 55 the Land Rover is still in its comfort zone and will cruise with throttle travel to spare for mild inclines.

The Series IIA is designed to carry around a third of a ton. It has leaf springs at all four corners. You can infer the quality of the ride from that. The springs on this example are relatively rare in being in good condition rather than having the leaves seized together. This means that on tarmac the suspension actually retains some flexibility and you get used to the tight, undulating bounce as you drive along. However any imperfections- joints in the tarmac, potholes, cats-eyes, manhole covers, white lines with too much paint – are transmitted straight to the chassis, the bodywork and the driver’s backside. The Landy crashes and thuds over bumps in a manner that would reduce a lesser vehicle to its component parts.

The Series IIA is designed to carry around a third of a ton. It has leaf springs at all four corners. You can infer the quality of the ride from that. The springs on this example are relatively rare in being in good condition rather than having the leaves seized together. This means that on tarmac the suspension actually retains some flexibility and you get used to the tight, undulating bounce as you drive along. However any imperfections- joints in the tarmac, potholes, cats-eyes, manhole covers, white lines with too much paint – are transmitted straight to the chassis, the bodywork and the driver’s backside. The Landy crashes and thuds over bumps in a manner that would reduce a lesser vehicle to its component parts.

The steering is low geared and, whilst unassisted (obviously) it isn’t excessively heavy even when stationary and once moving is actually a little on the the light side. Driving a Series Land Rover is often described as a suggestive rather than instructive experience but that’s because so many have had years of unchecked wear and play in their steering components. This one, with new joints and a properly adjusted steering box, tracks straight and true. The only quirk is the 20-degrees or so of free play around dead-centre and the initially unsettling habit of live-axled vehicles of jumping bodily sideways when hitting bumps at the wrong angle.

Braking is firmly rooted in the 1950s, being all-round drums with single leading shoes and no servo (it was optional but only on the softy Station Wagons which had silly things like interior lights and two-speed wipers…pah!). Given that the vehicle is cleared to tow over 3 tons they don’t inspire confidence even when confronted with the solo Landy with a 1.3-ton kerbweight. They require a firm shove to get any response and even when stamped on hard they could never be described as powerful. ‘Adequate given enough forward planning’ is probably the best way to put it. Fortunately the engine braking is very good but the gearbox also doesn’t like being rushed so it really is a case of planning ahead. In fact ‘doesn’t like to be rushed’ is a good summation of what the Series II Land Rover is about.

Braking is firmly rooted in the 1950s, being all-round drums with single leading shoes and no servo (it was optional but only on the softy Station Wagons which had silly things like interior lights and two-speed wipers…pah!). Given that the vehicle is cleared to tow over 3 tons they don’t inspire confidence even when confronted with the solo Landy with a 1.3-ton kerbweight. They require a firm shove to get any response and even when stamped on hard they could never be described as powerful. ‘Adequate given enough forward planning’ is probably the best way to put it. Fortunately the engine braking is very good but the gearbox also doesn’t like being rushed so it really is a case of planning ahead. In fact ‘doesn’t like to be rushed’ is a good summation of what the Series II Land Rover is about.

Driving a Series IIA for a day makes it very clear what the Land Rover’s good points are. It’s a simple, effective working tool that can be abused without fear of it breaking. It makes no concessions to the likings or wants of the driver if they get in the way of the job and it’s much happier to carting bags of fertiliser around a field that it is out on the open road. The whole vehicle feels dependable and eminently and endlessly fixable should anything go wrong. At the same time the downsides are just as obvious, the masochistic comfort levels, the intrusive and recalcitrant transmission, the poor road performance and the less-than-inspiring brakes being the most striking.

Ninety County Station Wagon – Carpets, Cloth and Cassettes

So now we take a big leap forward into the 1980s and jump into the driver’s seat of a 1990 Land Rover. I should state from the get-go that this is not an entirely fair comparison as this later model is a County Station Wagon (CSW to those who speak the lingo), the ‘County’ moniker denoting the very pinnacle of the Land Rover range at the time and being aimed squarely at people who valued comfort and convenience over the ability to hose out the insides of their Land Rover after a day in the fields. Thus, whilst the Series IIA was representative of your common-or-garden working Land Rover of the time, the CSW is not. None the less it is mechanically identical to any other Land Rover at the time and I shall try and judge it on those terms.

So now we take a big leap forward into the 1980s and jump into the driver’s seat of a 1990 Land Rover. I should state from the get-go that this is not an entirely fair comparison as this later model is a County Station Wagon (CSW to those who speak the lingo), the ‘County’ moniker denoting the very pinnacle of the Land Rover range at the time and being aimed squarely at people who valued comfort and convenience over the ability to hose out the insides of their Land Rover after a day in the fields. Thus, whilst the Series IIA was representative of your common-or-garden working Land Rover of the time, the CSW is not. None the less it is mechanically identical to any other Land Rover at the time and I shall try and judge it on those terms.

Looking at the Ninety from the outside the resemblance to the Series IIA is striking. The same basic outline is their- indeed in silhouette one would struggle to tell the difference. It’s still the two-box design with a bluff front end and a cavernous, almost cubic rear body seperated by a near-vertical windscreen. The Bache design elements such as the curved side and the rounded wingtops are still there. However there are several detail differences. Most obvious is the flush front end with plastic grille and headlamp bezels (it was the 1980s so they’re colour-matched on the County. On a more-working class example they would have been black plastic). If anything this heightens the overall squareness of the design. Large plastic wheelarch eyebrows now sprout from each corner. The Land Rover has grown a few inches in every dimension so the chunky proportions are the same, although the wheels (16-inch rims and 205-section tyres, just like the Series) now look a little lost under the more bulky bodywork. Bits of the chassis still extrude from various points and the front bumper is still a big square-section of steel, although it’s now painted rather than galvanised, as are the distinctive body cappings that give the aluminium bodywork its strength.

Looking at the Ninety from the outside the resemblance to the Series IIA is striking. The same basic outline is their- indeed in silhouette one would struggle to tell the difference. It’s still the two-box design with a bluff front end and a cavernous, almost cubic rear body seperated by a near-vertical windscreen. The Bache design elements such as the curved side and the rounded wingtops are still there. However there are several detail differences. Most obvious is the flush front end with plastic grille and headlamp bezels (it was the 1980s so they’re colour-matched on the County. On a more-working class example they would have been black plastic). If anything this heightens the overall squareness of the design. Large plastic wheelarch eyebrows now sprout from each corner. The Land Rover has grown a few inches in every dimension so the chunky proportions are the same, although the wheels (16-inch rims and 205-section tyres, just like the Series) now look a little lost under the more bulky bodywork. Bits of the chassis still extrude from various points and the front bumper is still a big square-section of steel, although it’s now painted rather than galvanised, as are the distinctive body cappings that give the aluminium bodywork its strength.

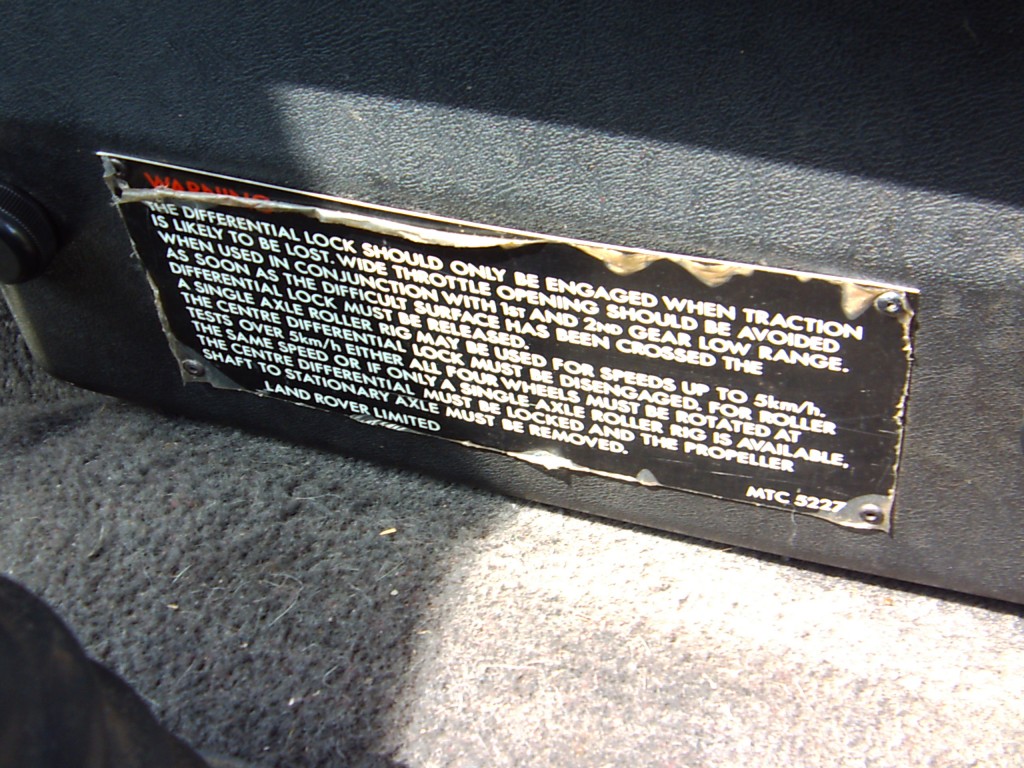

Inside it’s all change. Whilst the Series IIA was a swathe of matt-green metal the County has what is approaching a proper interior. The instruments migrated in front of the driver back in the 1970s on the Series III, which also introduced the full-width parcel shelf seen here but the Ninety and its relations really upped the game in regards to trim. The County has full-width grey carpeting on the floor and seat box whilst lesser models had thick vinyl mats. There’s a fabric headlining, tough plastic door cards and even neat plastic grilles over the windscreen flap vents. There’s much more switchgear than on the Series vehicle, belying an increase in gadgetry, and a pleasing amount of it comes from British Leyland cars of the period (column stalks from an Austin Ambassador are a highlight here). The dashboard consists of a speedo and three ancillary gauges (water temperature, fuel and a voltmeter) and a plethora of warning lights. The heater now lives under the bonnet rather than in the cabin and the self-cancelling indicator mechanism isn’t exposed for all to see. Equipment includes a clock, a heated rear window and wash/wipe, a cigar lighter and an interior light.

Inside it’s all change. Whilst the Series IIA was a swathe of matt-green metal the County has what is approaching a proper interior. The instruments migrated in front of the driver back in the 1970s on the Series III, which also introduced the full-width parcel shelf seen here but the Ninety and its relations really upped the game in regards to trim. The County has full-width grey carpeting on the floor and seat box whilst lesser models had thick vinyl mats. There’s a fabric headlining, tough plastic door cards and even neat plastic grilles over the windscreen flap vents. There’s much more switchgear than on the Series vehicle, belying an increase in gadgetry, and a pleasing amount of it comes from British Leyland cars of the period (column stalks from an Austin Ambassador are a highlight here). The dashboard consists of a speedo and three ancillary gauges (water temperature, fuel and a voltmeter) and a plethora of warning lights. The heater now lives under the bonnet rather than in the cabin and the self-cancelling indicator mechanism isn’t exposed for all to see. Equipment includes a clock, a heated rear window and wash/wipe, a cigar lighter and an interior light.

The seats themselves are sculpted, rather like the IIA’s Deluxe seats but have higher backs and include head restraints. On the County they’re trimmed in tweed cloth, which is much more pleasant in hot weather, but the Basic specification models had identical chairs trimmed in vinyl. A striking difference is the view out of the windscreen. The screen is now a one-piece item and is deeper, eating into a recess let into the roof panel. This small change makes a big difference to the visibility, removing entirely the ‘looking through a letter box’ feeling that the Series had in some situations.

The seats themselves are sculpted, rather like the IIA’s Deluxe seats but have higher backs and include head restraints. On the County they’re trimmed in tweed cloth, which is much more pleasant in hot weather, but the Basic specification models had identical chairs trimmed in vinyl. A striking difference is the view out of the windscreen. The screen is now a one-piece item and is deeper, eating into a recess let into the roof panel. This small change makes a big difference to the visibility, removing entirely the ‘looking through a letter box’ feeling that the Series had in some situations.

This Ninety has a 2.5-litre turbodiesel under the bonnet, closely related to the 2.25-litre engine found in the Series vehicles. After holding the key in the correct position to warm the glow plugs for a few seconds the engine fires up quickly with a gritty puff of smoke and settles into a steady beat. As you would expect, it’s nowhere near as whisper-quiet as the petrol unit in the older Land Rover but it is surprisingly refined as it chatters away it itself and very little vibration finds its way to the driver. The carpeting and the thick layers of sound deadending on the other side of the bulkhead are a big help here.

This Ninety has a 2.5-litre turbodiesel under the bonnet, closely related to the 2.25-litre engine found in the Series vehicles. After holding the key in the correct position to warm the glow plugs for a few seconds the engine fires up quickly with a gritty puff of smoke and settles into a steady beat. As you would expect, it’s nowhere near as whisper-quiet as the petrol unit in the older Land Rover but it is surprisingly refined as it chatters away it itself and very little vibration finds its way to the driver. The carpeting and the thick layers of sound deadending on the other side of the bulkhead are a big help here.

By this time Land Rovers were using the LT77 5-speed gearbox as also found in the Rover SD1, Triumph TR7, Range Rover and Freight Rover. It’s not a gearbox known for its slick shifting but it’s an improvement over the old Rover 4-speed box in most respects. Most, but not all. Whilst the Series gearbox had a tough shift requiring a firm hand you could at least find all the gears in the pattern. The LT77 has a wonderfully imprecise shift, despite the fact that the lever travels directly into the gearbox. 1st gear especially is a case of trial and error and then relying on muscle memory. The other gears aren’t so bad but there’s none of the satisfying feel of metal sliding into metal that you get with the IIA’s transmission. On the other hand the forces required are light and the gearbox makes none of the shrieks and whines that the old unit made. Another carry-over is the entirely gear-driven drivetrain so the clonks and backlash are still there when taking up drive and you can feel the innards of the transmission shifting back and forth as you come on and off the power. The clutch is still heavy by car standards but is a revelation after driving the Series – in fact I jumped straight from the IIA to the Ninety, put my foot on the clutch and jammed it straight to the floor in one movement so unprepared was I for the improvement.

By this time Land Rovers were using the LT77 5-speed gearbox as also found in the Rover SD1, Triumph TR7, Range Rover and Freight Rover. It’s not a gearbox known for its slick shifting but it’s an improvement over the old Rover 4-speed box in most respects. Most, but not all. Whilst the Series gearbox had a tough shift requiring a firm hand you could at least find all the gears in the pattern. The LT77 has a wonderfully imprecise shift, despite the fact that the lever travels directly into the gearbox. 1st gear especially is a case of trial and error and then relying on muscle memory. The other gears aren’t so bad but there’s none of the satisfying feel of metal sliding into metal that you get with the IIA’s transmission. On the other hand the forces required are light and the gearbox makes none of the shrieks and whines that the old unit made. Another carry-over is the entirely gear-driven drivetrain so the clonks and backlash are still there when taking up drive and you can feel the innards of the transmission shifting back and forth as you come on and off the power. The clutch is still heavy by car standards but is a revelation after driving the Series – in fact I jumped straight from the IIA to the Ninety, put my foot on the clutch and jammed it straight to the floor in one movement so unprepared was I for the improvement.

The immediate sensation is that the Ninety feels bigger than the Series. It is of course- 4 inches wider and a touch under 5 inches longer – but the difference feels much greater than that. I don’t know if it’s because the Ninety feels like you are sitting on top of it rather than inside it due to the taller windscreen and firmer seats or if it’s just because of the greater solidity of the vehicle (the Series IIA is built entirely out of single-skin panels whilst the Ninety has a more complex and stronger body structure) but its a surprisingly significant change.

Given that the Ninety weighs an extra 400kg over the IIA and has only 15 horsepower more you’d think the performance would be no better and you’d be right. Straight-line speed is virtually identical but that disguises where the real improvements are, which is in the later engine’s flexibility. Whilst the boost level is almost negligible (less than 10 PSI) the turbo spools up from very low speeds and the engine’s long stroke means that torque is always on tap. Unlike the IIA the torque delivery continues into the upper parts of the rev range, meaning that the engine actually has a power band rather than a single-speed power peak. More flexible it may be but the basic technique is the same of getting into the high gears as soon as possible. 5th gear is a useable down to 30 MPH. That extra gear is where the other differences come from- the later Landy tops out at a much higher speed simply because it has the ability to use a higher gear and this greatly improves refinement which makes it more acceptable to cruise at speeds that, whilst possible in the Series, aren’t really practical. The Ninety will cruise at 60MPH and will sit at 70 MPH all day provided that the hills aren’t too steep and the driver can afford the crippling fuel consumption that follows (although even at its worst the diesel is superior to the average figure from the IIA’s petrol engine). Whilst incredibly noisy by normal standards the Ninety gives none of the auditory assault that the Series vehicle does even at comparable speeds.

Given that the Ninety weighs an extra 400kg over the IIA and has only 15 horsepower more you’d think the performance would be no better and you’d be right. Straight-line speed is virtually identical but that disguises where the real improvements are, which is in the later engine’s flexibility. Whilst the boost level is almost negligible (less than 10 PSI) the turbo spools up from very low speeds and the engine’s long stroke means that torque is always on tap. Unlike the IIA the torque delivery continues into the upper parts of the rev range, meaning that the engine actually has a power band rather than a single-speed power peak. More flexible it may be but the basic technique is the same of getting into the high gears as soon as possible. 5th gear is a useable down to 30 MPH. That extra gear is where the other differences come from- the later Landy tops out at a much higher speed simply because it has the ability to use a higher gear and this greatly improves refinement which makes it more acceptable to cruise at speeds that, whilst possible in the Series, aren’t really practical. The Ninety will cruise at 60MPH and will sit at 70 MPH all day provided that the hills aren’t too steep and the driver can afford the crippling fuel consumption that follows (although even at its worst the diesel is superior to the average figure from the IIA’s petrol engine). Whilst incredibly noisy by normal standards the Ninety gives none of the auditory assault that the Series vehicle does even at comparable speeds.

The steering on the CSW is power-assisted (technically an optional extra but almost universally fitted to all Land Rovers sold in the UK). It’s a nice improvement but unlike the performance and noise levels it doesn’t transform the experience. The steering system itself is otherwise the same and the Ninety has the same light feel with a bit of slack around the mid-point. In fact I’d go as far as to say that I preferred the IIA’s steering out on the road. All Land Rovers have relatively little steering feedback to reduce kickback when off-road but the Ninety’s wheel feels almost totally disconnected from the road and it’s easy to enter a corner and find yourself misjudging how much lock is required, which never happens in the Series.

Where the later Land Rover wins hands down is the ride quality. Whilst being rated to a higher payload than the IIA the Ninety’s ride is vastly superior in every way. This, of course, is down to the switch from leaf springs to coil springs. The Ninety’s ride isn’t just good for a 4×4 utility vehicle, it’s good full stop. The back end, fitted with higher-rated springs, is prone to being a bit jittery when unladen. Speed humps and bit potholes can still crash through to the bodywork (which actually creates more noise than the Series due to all the plastic trim panelling rattling about) but even at tis worst it is more comfortable than the IIA can be. On a good surface the Ninety is planted and secure and the permanent four-wheel drive means that it can actually be hurried along a twisty section of road at speeds surprising for its bulk. The live axles are still there so you still get the odd skip-and-jump over undulates but the 4WD and the dampened steering help keep it in check here.

Where the later Land Rover wins hands down is the ride quality. Whilst being rated to a higher payload than the IIA the Ninety’s ride is vastly superior in every way. This, of course, is down to the switch from leaf springs to coil springs. The Ninety’s ride isn’t just good for a 4×4 utility vehicle, it’s good full stop. The back end, fitted with higher-rated springs, is prone to being a bit jittery when unladen. Speed humps and bit potholes can still crash through to the bodywork (which actually creates more noise than the Series due to all the plastic trim panelling rattling about) but even at tis worst it is more comfortable than the IIA can be. On a good surface the Ninety is planted and secure and the permanent four-wheel drive means that it can actually be hurried along a twisty section of road at speeds surprising for its bulk. The live axles are still there so you still get the odd skip-and-jump over undulates but the 4WD and the dampened steering help keep it in check here.

The brakes are massively upgraded in comparison to the Series IIA, being servo-assisted with discs on the front and big drums on the back. They start biting early and feel well up the dealing with the Ninety on its own and any load it can legally haul. In fact it’s easy to overdo thinga and lock up the lightly laden back wheels on any surface that isn’t perfectly dry or is slightly loose. The all-synchro gearbox, for all its shortcomings, downshifts well and the diesel engine offers huge amounts of engine braking on its own.

For all the similarities in looks the Ninety is so different and so superior to the IIA in refinement, comfort, performance and handling that to compare them is entirely redundant. It should be clear that under the largely unchanging skin the Land Rover changed hugely over the 20 years that seperate the two vehicles. However what’s more interesting is how much has stayed the same. Not only the looks but the general concept. They’re still built along the same lines from the same materials. A lot of the features, good and bad, remain. They’re both mechanically simple and tough. They can both be dismantled almost entirely with a simple set of spanners (included in the tool kit…). They both suffer from cramped cabins with terrible ergonomics. They both put off-road and low-speed ability ahead of on-road capability and refinement. They both have objectively terrible gearboxes. They both slowly cook the driver’s left foot with transmission heat. They both rock gently back and forth if you apply the handbrake on a hill. They both leak water in to the vehicle and oil out of it.

Which one’s best? It’s an easy one. The Ninety is objectively superior in every way as a working tool or just as a car to live with on a day-to-day basis. The Series IIA oozes character and charm from every rivet and if you like your driving to be an experience in and of itself or you revel in a challenge then there’s few other vehicles that can match it. Ninety for the head, Series II for the heart.

Nice article – thanks.

I recall driving one of the very first 90TD vans we had at work, in usual “company car driven by young field engineer” fashion it was driven flat out everywhere from day one.

I distinctly remember passing a police roadside speed trap on the M6 at Preston, with my foot buried hard into the rubber matting and the engine screaming itself toward oblivion. In a moments panic I realised it was too late to avoid yet more points – I looked at the speedometer to quickly calculate how much this would cost me only to realise I was only doing 60MPH

Haha! Good anecdote, thanks for sharing.