As should be clear by now, the main tenet of this blog is that the worst thing a car can be is boring, and that cars that are generally considered very bad can, in fact, be very interesting and worth appreciating on that level, if nothing else.

As should be clear by now, the main tenet of this blog is that the worst thing a car can be is boring, and that cars that are generally considered very bad can, in fact, be very interesting and worth appreciating on that level, if nothing else.

To that end I have enthused about how the Austin Allegro is really an engineering masterpiece, why the Citroen 2CV is better than a Mini, why the AMC Pacer was a good idea ruined at the last minute and why the VW Polo Mk2F messed things up by being better than its predecessor.

So what am I to make of a 1973 Triumph Toledo 1300? This is a car with, seemingly, no redeeming features at all either from the perspective of ‘so bad it’s good’ or just outright ‘good’. It’s a three-box saloon car with four doors, a boot, four seats, a tiny engine in the front, a four-speed gearbox in the middle and a beam axle in the back. It is, literally, a car with all the interesting bits taken out because it is based on one of the most interesting Triumphs ever made (the longitudinal engine/front-wheel drive 1300) but with all the quirky bits taken out. It is, really, an utterly generic ‘Seventies saloon car, but being old and British this means that it’s likely to be boring and flaky rather than boring but effective like a German or Japanese car.

I make no bones that I like my cars from a rather ‘techie’ perspective- hence my fascination with hydropneumatic Citroens and my utter disinterest in water-cooled Volkswagens. The Toledo has nothing for me here, so what is it going to be like to drive?

Outside

Before we get into that, let us consider the car’s appearance. It may be a generic three-box saloon but it’s a very tidy- no, pretty- design. As with most Triumphs the styling was the work of Michelotti and it was really just a quick revamp of the old round-headlamped 1300/1500 design. The Toledo has the little rectangular lights and thin, wide grille that was fashionable at the time (think Viva HC, Avenger, Cortina Mk2 and so on) and it works well. The styling has some sharp, defined creases like a finely tailored suit but there really is very little to get excited about.

Before we get into that, let us consider the car’s appearance. It may be a generic three-box saloon but it’s a very tidy- no, pretty- design. As with most Triumphs the styling was the work of Michelotti and it was really just a quick revamp of the old round-headlamped 1300/1500 design. The Toledo has the little rectangular lights and thin, wide grille that was fashionable at the time (think Viva HC, Avenger, Cortina Mk2 and so on) and it works well. The styling has some sharp, defined creases like a finely tailored suit but there really is very little to get excited about.

The exception is the rear end. The Toledo retained the short, stubby boot of its forebear and coupled to the subtle sloping rear roof line, which ends in a pronounced overhang over the slanted rear screen almost reminiscent of a rear spoiler; this gives the car an almost coupe-like appearance from certain angles. The boot itself is a decent size but, rather like an old Jaguar, the lid is designed so that it obscures most of the aperture even when fully open, limited the size of the objects you can fit through.

The exception is the rear end. The Toledo retained the short, stubby boot of its forebear and coupled to the subtle sloping rear roof line, which ends in a pronounced overhang over the slanted rear screen almost reminiscent of a rear spoiler; this gives the car an almost coupe-like appearance from certain angles. The boot itself is a decent size but, rather like an old Jaguar, the lid is designed so that it obscures most of the aperture even when fully open, limited the size of the objects you can fit through.

This particular example is resplendent in Mallard Green, an unexpectedly tasteful green/blue/black colour which contrasts with the chrome and polished steel bumpers and trim parts. Like most ‘Seventies Triumphs the Toledo has ‘over riders’ on the front bumper that actually sit below and behind the bumper, thus performing no useful function whatsoever. The Toledo also suffers from British Leyland’s habit of a different font for every badge- the centre of the grille bears a ‘Toledo’ badge in a nice Swingin’ Sixties rounded text while the boot badge used chunky block capitals. Similarly the Triumph badge on the bonnet lip is in italics while the one on the back is upright. This is an incredibly minor thing to quibble over but I have a pet theory that it was just as much the failure to get the little details right that did for the reputation of BL’s products than any of the big and famous problems. We will touch on this subject later on. In fact, right now.

This particular example is resplendent in Mallard Green, an unexpectedly tasteful green/blue/black colour which contrasts with the chrome and polished steel bumpers and trim parts. Like most ‘Seventies Triumphs the Toledo has ‘over riders’ on the front bumper that actually sit below and behind the bumper, thus performing no useful function whatsoever. The Toledo also suffers from British Leyland’s habit of a different font for every badge- the centre of the grille bears a ‘Toledo’ badge in a nice Swingin’ Sixties rounded text while the boot badge used chunky block capitals. Similarly the Triumph badge on the bonnet lip is in italics while the one on the back is upright. This is an incredibly minor thing to quibble over but I have a pet theory that it was just as much the failure to get the little details right that did for the reputation of BL’s products than any of the big and famous problems. We will touch on this subject later on. In fact, right now.

Inside

In my Stag road test I mentioned that Triumph was one of the few components of British Leyland that managed to have something approaching an actual ‘house style’ for their cars, inside and out. Nowhere is this more evident that the inside of the Toledo, which would be immediately familiar to any Spitfire IV, Dolomite, Stag or 2500 driver. In contrast to the monastic minimalism of an Issigonis Austin or Morris the Toledo’s dashboard is luxurious in the extreme, with big slabs of veneered wood and no less than five dials and a warning light cluster (the ‘pie chart’ that found a home in all of Triumph’s products of the time). There’s no brown velour or green Formica here- the thickly-padded seats are plain dark blue cloth with black vinyl facings. The carpets and door trims are more black vinyl, as is the dash top and the window ledges are capped with slabs of stained wood (which don’t appear to have been sanded smooth…). Triumph’s signature white headlining is there which helps brighten the place up a bit and stops the relatively low roof line feeling claustrophobic. The ‘eyeball’ air vents at each front corner- another Triumph design feature- are present and correct.

In my Stag road test I mentioned that Triumph was one of the few components of British Leyland that managed to have something approaching an actual ‘house style’ for their cars, inside and out. Nowhere is this more evident that the inside of the Toledo, which would be immediately familiar to any Spitfire IV, Dolomite, Stag or 2500 driver. In contrast to the monastic minimalism of an Issigonis Austin or Morris the Toledo’s dashboard is luxurious in the extreme, with big slabs of veneered wood and no less than five dials and a warning light cluster (the ‘pie chart’ that found a home in all of Triumph’s products of the time). There’s no brown velour or green Formica here- the thickly-padded seats are plain dark blue cloth with black vinyl facings. The carpets and door trims are more black vinyl, as is the dash top and the window ledges are capped with slabs of stained wood (which don’t appear to have been sanded smooth…). Triumph’s signature white headlining is there which helps brighten the place up a bit and stops the relatively low roof line feeling claustrophobic. The ‘eyeball’ air vents at each front corner- another Triumph design feature- are present and correct.

The driving position is quite upright (almost Mini-like) but otherwise the driving position is very modern. The pedals are, unusually for a classic Triumph, in front of the driver’s feet and in line with the steering wheel. The gear lever (made of wood effect plastics, in a shade of orange that I’m sure no tree has ever been in real life) falls nicely to hand and you can see most, although not all, of the dials while holding the steering wheel. The major switchgear is neatly arranged along the bottom of the dashboard and all the switches share the same basic look, at odds to the random array of switches, toggles and buttons that were scattered at random across the dashboard of an ADO16 or an Allegro from the same period.

The driving position is quite upright (almost Mini-like) but otherwise the driving position is very modern. The pedals are, unusually for a classic Triumph, in front of the driver’s feet and in line with the steering wheel. The gear lever (made of wood effect plastics, in a shade of orange that I’m sure no tree has ever been in real life) falls nicely to hand and you can see most, although not all, of the dials while holding the steering wheel. The major switchgear is neatly arranged along the bottom of the dashboard and all the switches share the same basic look, at odds to the random array of switches, toggles and buttons that were scattered at random across the dashboard of an ADO16 or an Allegro from the same period.

Because this is a car from the ‘Seventies the little Triumph has one ashtray per person. The Toledo doesn’t have the incredible sense of space of a BMC product but neither is it cramped. This is particularly impressive considering that it is a front-wheel drive design turned into a rear-wheel drive one.

Because this is a car from the ‘Seventies the little Triumph has one ashtray per person. The Toledo doesn’t have the incredible sense of space of a BMC product but neither is it cramped. This is particularly impressive considering that it is a front-wheel drive design turned into a rear-wheel drive one.

What is even more impressive is the generally feeling of quality. The doors shut with a solid ‘thunk’ that comes as a complete surprise to those of us used to the wheelie-bin like flapping of a Mini door. The panels and trim parts are all securely

On the Move

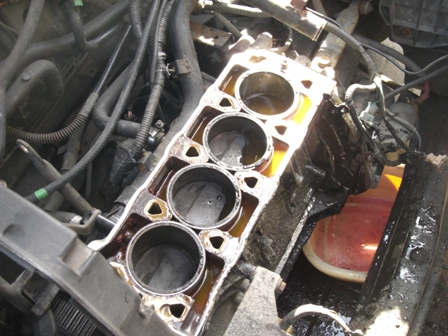

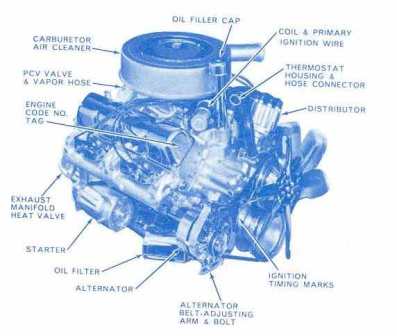

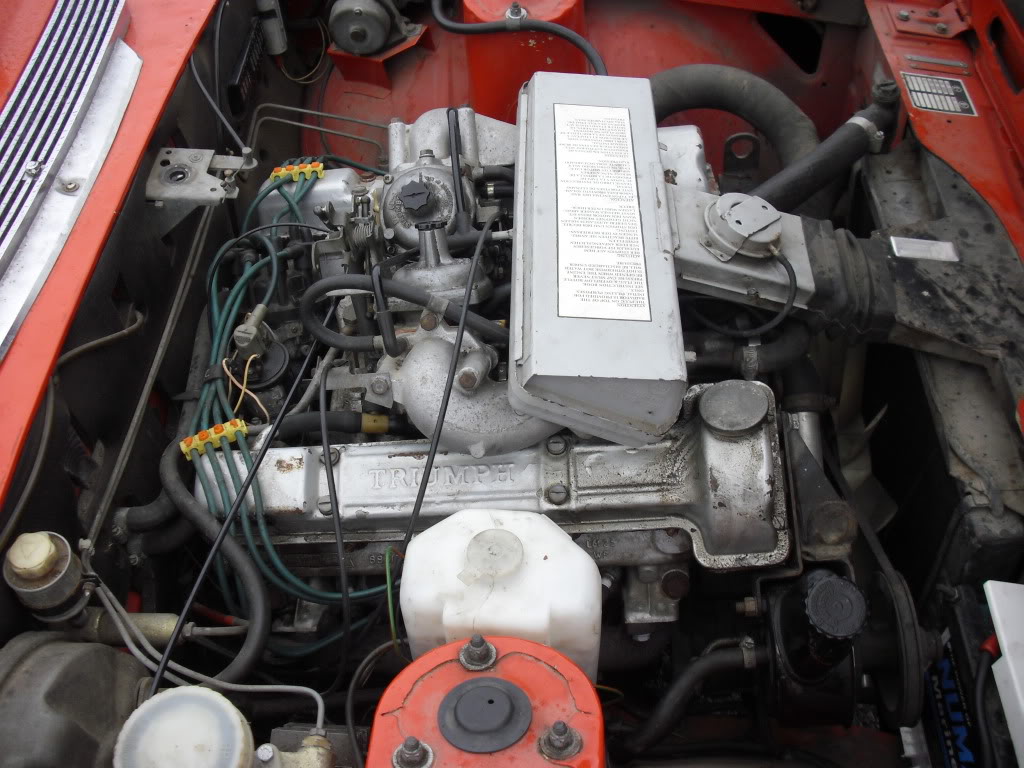

The little 1.3-litre four-cylinder engine fires up quickly with a dab of choke. This engine has its origins in the days of the Standard Eight and then went on to power the Herald and Spitfire with great success. It has no design features of note other than that the oil filler cap is at the back of the rocker cover rather than the front and it is renowned for sounding like it has loose tappets and a worn camshaft even when in perfect nick. This particular Toledo has just less than 45,000 miles on it and this engine is pretty quiet by Triumph 4-pot standards but still has a definite rattle. Otherwise it is smooth and quiet with just a rasp from a (possibly slightly leaky) exhaust and a bit of fan whine.

The little 1.3-litre four-cylinder engine fires up quickly with a dab of choke. This engine has its origins in the days of the Standard Eight and then went on to power the Herald and Spitfire with great success. It has no design features of note other than that the oil filler cap is at the back of the rocker cover rather than the front and it is renowned for sounding like it has loose tappets and a worn camshaft even when in perfect nick. This particular Toledo has just less than 45,000 miles on it and this engine is pretty quiet by Triumph 4-pot standards but still has a definite rattle. Otherwise it is smooth and quiet with just a rasp from a (possibly slightly leaky) exhaust and a bit of fan whine.

The clutch is light but this example suffers from a rather hard take-up and more than a little judder. The gearbox, which would later go on to see service in the Morris Marina, is very pleasant to use. It’s by no means a sporty box to use but it has a light, tactile action and it’s easy to navigate between speeds.

The clutch is light but this example suffers from a rather hard take-up and more than a little judder. The gearbox, which would later go on to see service in the Morris Marina, is very pleasant to use. It’s by no means a sporty box to use but it has a light, tactile action and it’s easy to navigate between speeds.

The first thing that’s noticeable about the Toledo when pulling away is the remarkable lack of anything that could really be described as performance. The engine is willing and pulls very smoothly and evenly throughout its rev range, but with only 60 horsepower at best this is never going to translate into brisk acceleration. The Toledo trots along smartly enough in the lower two gears but after shifting into third the car gathers speed with some effort. In fast traffic or in a hilly area you need to work the engine hard with lots of use of full throttle and extensive use of the rev range. This particular Toledo has an interesting niggle in that the rev counter briefly sticks at the 3,500 rpm mark which doesn’t help the impression of speed.

None the less, given enough road and a lack of inclines the Toledo will continue to gently gather momentum until it reaches the national speed limit. At these sorts of speeds the other issue is the low gearing but there’s no way the engine could pull anything higher so that is to be expected. The motor is spinning at 4,250rpm at 70mph so refined cruising is off the cards. It will happily maintain that all day, even if it does require some careful forward-planning to avoid the need to lift off for even a fraction of a second, which would mean starting the business of acceleration all over again.

What this talk of performance disguises is how generally competent the Toledo is at everything else. It drives very smoothly. It’s comfortable. It handles very sweetly. This is really the biggest surprise but it shouldn’t be when you remember that it is a Triumph, even if it is the most boring and least sporty one ever made. It may have a rear beam axle held in place by trailing arms made from I-section beams that look suspiciously like off-cuts found in a skip round the back of a warehouse in Canley but it is coil sprung and at the front is Triumph’s well-proven double-wishbone independent suspension. Coupled to the direct and nicely-weighted steering this makes the Toledo surprisingly ‘chuckable’. It handles very well and I don’t mean this in the “No, it does handle well and here’s a 2,000 word engineering essay explaining exactly why even if it doesn’t really feel like it” that Hydragas cars ‘handle well’. It’s just a nicely balanced and grippy rear-wheel drive saloon car. Certainly this is a car where the handling is far more capable than it has any need to be given the modest performance. Despite the presence of a front anti-roll bar the little Triumph rolls quite a bit but it keeps on gripping and this is crucial to maintaining crucial momentum.

What this talk of performance disguises is how generally competent the Toledo is at everything else. It drives very smoothly. It’s comfortable. It handles very sweetly. This is really the biggest surprise but it shouldn’t be when you remember that it is a Triumph, even if it is the most boring and least sporty one ever made. It may have a rear beam axle held in place by trailing arms made from I-section beams that look suspiciously like off-cuts found in a skip round the back of a warehouse in Canley but it is coil sprung and at the front is Triumph’s well-proven double-wishbone independent suspension. Coupled to the direct and nicely-weighted steering this makes the Toledo surprisingly ‘chuckable’. It handles very well and I don’t mean this in the “No, it does handle well and here’s a 2,000 word engineering essay explaining exactly why even if it doesn’t really feel like it” that Hydragas cars ‘handle well’. It’s just a nicely balanced and grippy rear-wheel drive saloon car. Certainly this is a car where the handling is far more capable than it has any need to be given the modest performance. Despite the presence of a front anti-roll bar the little Triumph rolls quite a bit but it keeps on gripping and this is crucial to maintaining crucial momentum.

For all its sporting pedigree the car rides very well. It has the classically British setup of soft springing and tight damping meaning that isolated bumps and cambers don’t really make it through to the interior yet the car doesn’t feel wallowy or uncontrolled. Really scabby rural lanes can make the back end get skittish, as you’d expect from a live axle, and a big pothole taken at the wrong angle can induce a bit of bump-steer but otherwise it is very stable. Even over very lumpy and bumpy bits of tarmac the interior’s quality of fit and finish holds true with no rattles or squeaks to speak of.

Conclusion

Before driving the Toledo I had very little opinion of the small Triumph saloons, but after covering 500 miles on all sort of roads, from pottering around rural lanes to a 200-mile motorway jaunt, I will stick my neck out and say that the Toledo/Dolomite may well be the best British Leyland car there is.

It’s not technically impressive but that is part of what makes it so good. It is just a conventional car done very well with neat styling, a reliable engine, a nice gearbox, decent suspension and solid build quality.

It’s not technically impressive but that is part of what makes it so good. It is just a conventional car done very well with neat styling, a reliable engine, a nice gearbox, decent suspension and solid build quality.

A lot of people talk of Triumph as the ‘British BMW’. In that analogy the Dolomite is the 3-Series, the 2500 is the 5-Series and the TR is a Z4. I generally don’t like trying to pin down modern equivalents of classic cars because things have changed so much and it creates unrealistic expectations, but here the comparison is too good to pass up. The Dolomite Sprint is the ‘Seventies version of the BMW M3- a small saloon with race-bred performance and some extravagant styling that helps define the maker’s image. But for every M3 BMW sells today they sell dozens of 318 diesels which could never be described as sporty or fast but which reap the benefits of their maker’s experience to just be sound, pleasant to drive cars for ordinary people. This is what the Toledo 1300. The only real criticism of it is that it is very, very slow but that’s because it was the base model of an extensive range. If you wanted a faster Toledo you bought a 1500 or a 1500TC. If you wanted something with a bigger boot and a dash of sporty style you opted for a Dolomite.

As I mentioned earlier it is the little things that come together to make the Toledo such a capable car. It has an excellent heater and decent fresh air ventilation. It has enough oddments storage to be practical on a long motorway journey. You can hear the radio (Radio 4, Radio 5 and a dozen French music stations on Long Wave) even at a frantic 70mph. It has a heated rear window that works. Uniquely amongst classic cars that I’ve experienced the filler neck will accept the full flow of a petrol pump nozzle and then cut it off when full without discharging a litre or so down the side of the rear wing. It has servo brakes with discs on the front wheels. You can take a 270-degree motorway slip-road at 50mph without worrying that you’ll either slide or fall over. Really it’s a vehicle with all the charm of a classic and all the day-to-day practicality of a modern car.

Compliments don’t really come higher than that.

I mentioned in my Morris retrospective that there is a pleasing irony to the whole story that a former part of the Nuffield empire (the Pressed Steel works at Cowley, now BMW Plant Oxford) is busy churning out cars with a name derived from a Morris product (the Mini-Minor), complete with a grille design based on the one developed to distinguish the ‘lesser’ Morris Minis from their Austin counterparts/competitors.

I mentioned in my Morris retrospective that there is a pleasing irony to the whole story that a former part of the Nuffield empire (the Pressed Steel works at Cowley, now BMW Plant Oxford) is busy churning out cars with a name derived from a Morris product (the Mini-Minor), complete with a grille design based on the one developed to distinguish the ‘lesser’ Morris Minis from their Austin counterparts/competitors. I have no qualms about talking about the MINI as a design, though, and that’s where most of my problem with it lies. It simply lacks the technological and design innovation that made its forebear so iconic and successful. The Mini was a clever car designed on ruthlessly functional lines. The MINI is an ordinary car designed around its styling- the complete polar opposite. Yes, that styling is a pretty good update of the original but that’s not what the Mini was about. However I do like the similarity that, while the Mini’s functional looks worked superbly on a small car they just didn’t when applied to larger cars like the 1800 and the Maxi. The MINI suffers the same problem- it’s a neat enough exercise on the original product but applied to the Countryman/Paceman models it makes a Landcrab look elegant and suave.

I have no qualms about talking about the MINI as a design, though, and that’s where most of my problem with it lies. It simply lacks the technological and design innovation that made its forebear so iconic and successful. The Mini was a clever car designed on ruthlessly functional lines. The MINI is an ordinary car designed around its styling- the complete polar opposite. Yes, that styling is a pretty good update of the original but that’s not what the Mini was about. However I do like the similarity that, while the Mini’s functional looks worked superbly on a small car they just didn’t when applied to larger cars like the 1800 and the Maxi. The MINI suffers the same problem- it’s a neat enough exercise on the original product but applied to the Countryman/Paceman models it makes a Landcrab look elegant and suave. I will quickly reiterate that I don’t criticise or deny the MINI’s success as a product. Rover and BMW’s business logic in going down the retro route can’t be faulted and neither can the resulting car be called anything other than a global (and British-built) sales success. It just grates slightly that it’s with such a cynical and superficial product which uses the badge of a car that started out something wholly non-cynical and non-superficial.

I will quickly reiterate that I don’t criticise or deny the MINI’s success as a product. Rover and BMW’s business logic in going down the retro route can’t be faulted and neither can the resulting car be called anything other than a global (and British-built) sales success. It just grates slightly that it’s with such a cynical and superficial product which uses the badge of a car that started out something wholly non-cynical and non-superficial. So that is a brief introduction to Why I Can’t Stop Moaning And Love The MINI.

So that is a brief introduction to Why I Can’t Stop Moaning And Love The MINI. So there you have it. I’ve been thinking about this all wrong. The MINI isn’t the successor to the Mini at all. It’s actually a follow-up act to the Minor

So there you have it. I’ve been thinking about this all wrong. The MINI isn’t the successor to the Mini at all. It’s actually a follow-up act to the Minor