When it was founded in 1967 British Leyland became the proud owner of approximately 35 manufacturing brands covering cars, vans, commercial vehicles, fork-lift trucks, fridges, body pressings manufacturers and carburettor makers. As of 2012 half a dozen are still in active use, none of them in independent British ownership.

When it was founded in 1967 British Leyland became the proud owner of approximately 35 manufacturing brands covering cars, vans, commercial vehicles, fork-lift trucks, fridges, body pressings manufacturers and carburettor makers. As of 2012 half a dozen are still in active use, none of them in independent British ownership.

Clearly BL managed to screw over quite a few famous names during its 19-year existence. In fact it’s a tough choice to decide which company was most thoroughly wrecked by its association with the Flying Plughole. I’ve already mentioned that Morris was sidelined, for all its track record of innovation, in favour of dull, conservative Austin by BMC. Then there was Triumph which in the early ‘Seventies was close to becoming a British equivalent of BMW but within a decade was reduced to one model which was a rebadged Honda Ballade. MG was once estimated to be one of the top three most valuable brands in the world but now is a tiny bit player on the global market gracing the bonnet of some Chinese built B-segment family cars.

However, on consideration, the brand that suffered most at the hands of the Lancashire Leviathan was Rover. I can hear the sniggering coming over my WiFi right now. Rover? Makers of dodgy little wood-encrusted shopping saloons beloved of pensioners and Alan Partridge? Yes. That’s the company.

Or more accurately- No. That’s not the company at all. That’s the lurching zombie-like carcass of the company in its final lunges before it was finally decapitated and laid to rest. If, when you hear the word ‘Rover’ you think of this:

Or this:

Then come with me on a wonderful journey of discovery.

Then come with me on a wonderful journey of discovery.

Let’s start in 1948. Rover has just launched the P3 model, a lightly warmed-over version of its pre-war car. Despite the austerity the P3 is a hit with the professional classes and a string of Royal Warrants and celebrity buyers soon followed.

I know this doesn’t sound very impressive so far. In fact it all sounds rather ‘Rover’- a small, struggling company that carved out a niche making cars full of burred walnut and beige leather for Tory-voting upper management types. Bear with me, though, because it will get interesting.

Crucially, during the war Rover had been co-opted into helping some eccentric boffin called Frank Whittle help build some crazy new design for an aircraft engine with no propellers that ran on its own exhaust gases that he’d dreamt up. As it turned out Rover and Whittle didn’t get on, mainly because Rover refused to accept that he knew more about jet engines than they did, despite being the man who had invented them in the first place. The company’s engineers kept modifying Whittle’s designs to their own preferences and in the end he jumped ship to go and work with Rolls-Royce. Which is now the second biggest builder of aero-engines in the world. Nice going Rover.

Necessity is, they say, the mother of invention and the story of how the need to kick-start production from scratch in a world of post-war austerity led to Rover creating a best-selling 4×4 is well known so I won’t go into it now. I don’t know if it was the brief fling at the cutting edge of technology with Whittle, the complete fresh start allowed for by the switch to a new factory (the original one in Coventry had been Blitzed), the steady income provided by the Land Rover or whether there’s something in the water in Solihull but from 1948 onwards Rover went a bit mental. They ran with the gas turbine idea and after only a few years, whilst Whittle and Rolls-Royce were still ironing the bugs out the aerial jet engines, Rover were building and selling their own turbines for industrial use.

Back on the roads the company unveiled its P4 model in 1949. The P4 came to be known as such an eminently respectable car that it has been dubbed the ‘Auntie’ but placed in the context of Britain in the ‘Forties it’s semi-streamlined styling and dramatic Cyclops central headlamp was daring and brash. Rovers were still all leather, walnut, grey and beige but they were increasingly innovative under the skin. The P4s had freewheel transmission and Rover’s peculiar Inlet-over-Exhaust layout engines with their wedge-shaped combustion chambers and Weslake-designed cylinder heads. The Series II P4 introduced the Rover’s own brand of semi-automatic manual transmission. Called the ‘Roverdrive’ it was a strange 2-speed box with a separate overdrive third speed and a manual clutch. It was best thought of as a cross between a traditional Wilson pre-selector and a modern automated manual system. Unsurprisingly it wasn’t terribly popular but it worked.

In the meantime Rover had been (at times literally) blazing a trail with its gas turbine powered cars. Rover wasn’t the only company to be enticed by the turbine’s power, light weight and reliability but their wartime experience had given them a head start. The famous JET 1 car, looking like a rather dashing roadster version of a P4, was unveiled in 1950 and was the world’s first turbine-powered car. It packed 230 horsepower and could do over 150 miles an hour. A whole series of ‘T Cars’ (T for turbine) followed, including the T3 of 1956. This was not only the first car to be expressly designed for a turbine powerplant but it also had four-wheel drive and all-round disc brakes.

In the meantime Rover had been (at times literally) blazing a trail with its gas turbine powered cars. Rover wasn’t the only company to be enticed by the turbine’s power, light weight and reliability but their wartime experience had given them a head start. The famous JET 1 car, looking like a rather dashing roadster version of a P4, was unveiled in 1950 and was the world’s first turbine-powered car. It packed 230 horsepower and could do over 150 miles an hour. A whole series of ‘T Cars’ (T for turbine) followed, including the T3 of 1956. This was not only the first car to be expressly designed for a turbine powerplant but it also had four-wheel drive and all-round disc brakes.

Rover then teamed up with racing car constructor BRM to enter a series of turbine-powered cars in the 24Hr Le Mans races. The cars were thirsty and suffered a few reliability hiccups but were dazzlingly fast, setting average speeds of over 100 MPH.

Rover then teamed up with racing car constructor BRM to enter a series of turbine-powered cars in the 24Hr Le Mans races. The cars were thirsty and suffered a few reliability hiccups but were dazzlingly fast, setting average speeds of over 100 MPH.

In less exotic, but related work, Rover had designed its own diesel engine for the Land Rover which was only the third small-capacity road-going diesel engine to enter production. To try and extract more power from their new engine Rover used their turbine experience to build a turbocharger for it and then added an intercooler. Prototype 2.5-litre turbo-intercooled engines were running around Solihull about twenty years before any other car manufacturer introduced them and a good 35 years before Land Rover would get around to putting a very similar engine into production.

By this time the glorious P5 was on the scene. Originally intended as a P4 replacement the P5 ended up being a much bigger, grander car, with a front end like a baleen whale hoovering up small fry. It exemplified the solid but strangely modern vibe that Rover were giving off with its Rostyle sculpted wheel trims, minimalist dashboard (including a tool set in a drawer), and its enticing styling combination of sheer sides and rounded edges.

The real stylistic coup came in 1962 when the Series II P5 brought with it the ‘Coupe’ version. Anticipating by 40 years the modern trend amongst German manufacturers for chopped-down saloon the P5 Coupe was still a four-door with ample rear space but it had a lower roofline with more steeply raked front and rear glass and a natty chrome ‘swoosh’ on the rear quarter panel. It remains, in my opinion, one of the best looking cars ever made because it somehow managed to look both imposing and sleek at the same time.

The real stylistic coup came in 1962 when the Series II P5 brought with it the ‘Coupe’ version. Anticipating by 40 years the modern trend amongst German manufacturers for chopped-down saloon the P5 Coupe was still a four-door with ample rear space but it had a lower roofline with more steeply raked front and rear glass and a natty chrome ‘swoosh’ on the rear quarter panel. It remains, in my opinion, one of the best looking cars ever made because it somehow managed to look both imposing and sleek at the same time.

The P5 set out the fundamentals of a ‘real’ Rover- heavy, bluff, luxurious but modern. If Triumph was the British BMW then Rover in the ‘Sixties was the British Mercedes. Not exactly sporty but powerful. Sort of like a muscle car but with burred wood panelling and art-deco light fittings.

Hot on the heels of the P5 Coupe came the real groundbreaker. If Rover was now renowned for the quality of its vehicles and its pioneering work with jet engines no one could really say that its production cars were innovative. Modern, yes. Clever, yes. But more on the edges of the box rather than outside it.

Hot on the heels of the P5 Coupe came the real groundbreaker. If Rover was now renowned for the quality of its vehicles and its pioneering work with jet engines no one could really say that its production cars were innovative. Modern, yes. Clever, yes. But more on the edges of the box rather than outside it.

Rover’s post-war ideas blitz was only just getting into top gear though. The eventual replacement for the P4, unsurprisingly dubbed the P6, was a real gamechanger. It was a 2-litre 4-cylinder saloon pitched firmly into a market dominated by 6-cylinder Fords, Hillmans and Morrises. By being faster and better-handling than any of them the P6, combined with the similar (but completely independent) Triumph 2000, which came out one week after the Rover, created the idea of an ‘executive saloon’ from scratch. Before the P6 luxury saloons were just more comfortable versions of normal ones but with an extra couple of cylinders and more chrome. They competed on luxury rather than performance. The small Rover knobbled them on both counts.

The P6 has been called ‘the British DS’ and although this sounds like someone getting a little carried away but it really isn’t that far from the truth. Just as the DS was a showcase for everything cutting edge that the French motor industry could concoct, so was the P6. Famously its original design incorporated a gas turbine. Like everyone who tried a jet-powered road car Rover just couldn’t solve the horrendous fuel economy at anything other than full speed, the slow power delivery or the road-melting exhaust temperatures.

The P6 has been called ‘the British DS’ and although this sounds like someone getting a little carried away but it really isn’t that far from the truth. Just as the DS was a showcase for everything cutting edge that the French motor industry could concoct, so was the P6. Famously its original design incorporated a gas turbine. Like everyone who tried a jet-powered road car Rover just couldn’t solve the horrendous fuel economy at anything other than full speed, the slow power delivery or the road-melting exhaust temperatures.

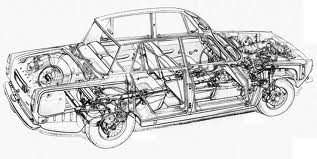

None the less the P6 still had a unique skeleton monocoque where all the external body panels were hung on an immensely strong structural frame. To provide clearance for the gas turbine engine the front suspension was by independent coil springs mounted horizontally along the top of the inner wings connected to the wheels by bell-cranks and push-rods, just like a modern racing car. At the rear was a De Dion rear axle with inboard disc brakes. The new engine that did get under the bonnet was an overhead-cam four-cylinder with a ‘heron head’ design.

The styling and design, by the masterful David Bache, was also revolutionary. Here the DS metaphor really starts to work because the P6 has the same basic teardrop profile with a low, straight nose, a kicked-up rear cabin and a strangely truncated, hunched back end. Whilst the DS is all curves the P6 is straight lines and creases with a wide, low stance. Inside it had a stark, clean look unlike the ‘Pall Mall Club’ atmosphere of the P4. The P6 was a well-deserved success and it became the first European Car of the Year. Rover’s roll just kept continuing and indeed gathered more pace throughout the ‘Sixties.

With mechanical and stylistic innovation now firmly established as a corporate trait Rover weren’t going to let up. Whilst the P6’s suspension was world-leading the company was looking enviously at Citroen’s hydropneumatic system. The combination of ride comfort and handling would be perfect for the new breed of Rover but the bounce and roll exhibited by any big Citroen when asked to make ‘progress’ along a twisty road would not do.

With mechanical and stylistic innovation now firmly established as a corporate trait Rover weren’t going to let up. Whilst the P6’s suspension was world-leading the company was looking enviously at Citroen’s hydropneumatic system. The combination of ride comfort and handling would be perfect for the new breed of Rover but the bounce and roll exhibited by any big Citroen when asked to make ‘progress’ along a twisty road would not do.

Working in partnership with Automotive Products Rover developed its own variant on the hydropneumatic suspension system. Like the Citroen version this was based around spherical springs of compressed nitrogen gas and pressurised hydraulic fluid. This was connected to the wheel by a hydraulic strut which continuously adjusted the ride height to account for any additional weight in the car. The key development was a mechanical link arm and a hydraulic metering valve. Somehow (despite looking at the drawing of how it’s supposed to work I still can’t fathom it) this allowed the system to tell the difference between suspension movement caused by a bump in the road and movement caused by body roll. It could assist former and completely restrict the latter, meaning that the car cornered perfectly level even at high speeds but soaked up huge bumps and potholes with ease. The AP/Rover hydraulic suspension was fitted to a P6 and found to be perfectly workable.

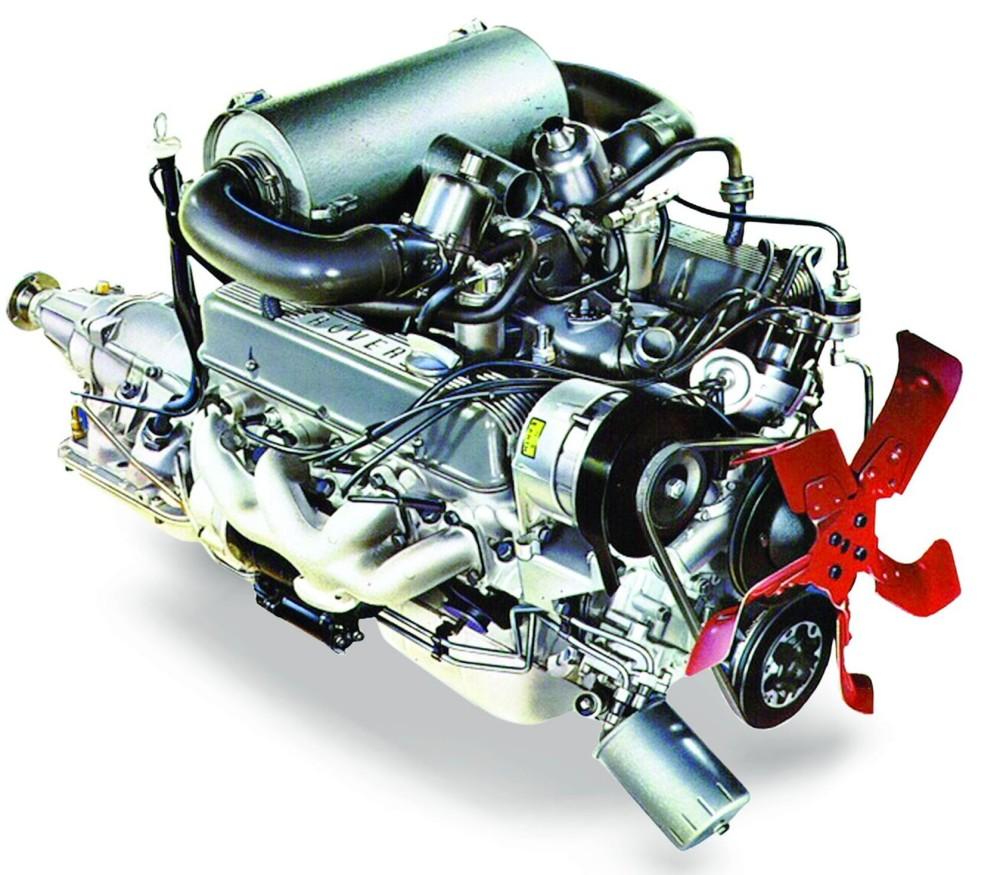

In more prosaic matters, in 1967 along came the object with which Rover was to be most associated, the 3.5-litre V8 engine. This, of course, came courtesy of General Motors who had designed it in the 1950s. In turbocharged ‘Jetfire’ form it became the first engine to reach the magic figure of one horsepower per cubic inch of displacement (215 in this case). But the engine was too small for the American market and in naturally-aspirated form didn’t produce enough power. Its all-alloy construction was highly advanced but flawed production methods at The General caused reliability problems that tarnished the engine’s reputation. It was just the thing for the new, reformed Rover and they quickly ironed out the bugs and dropped into the P5 and P6, producing the P5B ‘3.5-litre’ and the P6B ‘3500’, because decimal points are clearly the sign of true class.

In more prosaic matters, in 1967 along came the object with which Rover was to be most associated, the 3.5-litre V8 engine. This, of course, came courtesy of General Motors who had designed it in the 1950s. In turbocharged ‘Jetfire’ form it became the first engine to reach the magic figure of one horsepower per cubic inch of displacement (215 in this case). But the engine was too small for the American market and in naturally-aspirated form didn’t produce enough power. Its all-alloy construction was highly advanced but flawed production methods at The General caused reliability problems that tarnished the engine’s reputation. It was just the thing for the new, reformed Rover and they quickly ironed out the bugs and dropped into the P5 and P6, producing the P5B ‘3.5-litre’ and the P6B ‘3500’, because decimal points are clearly the sign of true class.

The now-Rover V8 put clear water between Triumph and Jaguar, who were rapidly cashing in on the market that Rover had created and the combination of power and refinement was perfectly in keeping with the company’s more dynamic image. It’s worth quickly mentioning that before the V8 turned up Rover were in the final stages of developing a 5-cylinder version of the 2000 engine which proved entirely practical. About ten years before Audi did it.

The now-Rover V8 put clear water between Triumph and Jaguar, who were rapidly cashing in on the market that Rover had created and the combination of power and refinement was perfectly in keeping with the company’s more dynamic image. It’s worth quickly mentioning that before the V8 turned up Rover were in the final stages of developing a 5-cylinder version of the 2000 engine which proved entirely practical. About ten years before Audi did it.

Things were about to get a whole lot more dynamic though because, having invented a whole new type of saloon car Rover then set about redefining two more market areas. One of these was a project to create a more comfortable Land Rover which ended up becoming something called the Range Rover. I don’t really need to go in to that other than to hold it up a shining example of the independent Rover Company’s sheer bloody genius.

The other was a supercar. A Rover supercar. A. Rover. Supercar. That that phrase sounds so ridiculous now shows how far the brand’s stock has fallen. In fact it was never going to be badged as a Rover, but as an Alvis, which Rover had bought in 1965 (this was back in the days when Rover bought other companies rather than being endlessly bought out itself). It was developed as the P6BS and, as the name suggests, was loosely based around the P6. It used a tuned 3.5-litre V8 mounted mid/rear driving the rear axle through a mid-mounted gearbox. The cabin had three seats (two in the front and central rear) and, almost uniquely amongst supercars, excellent near-360-degree visibility. The P6BS was worked up into a fully driveable, practical prototype. All it needed for production was some proper styling. That was well underway (under the P9 project name) when, in 1967, Rover was purchased by the Leyland Motor Corporation. A year later the LMC merged with British Motor Holdings to create British Leyland, bringing Rover, Jaguar and Triumph under one roof.

So, at 2,500 words, I will now take a break. Let’s leave Rover under new management but with a world-leading mid-sized saloon, a much-loved big saloon, a supercar and a ground breaking 4×4. Sadly, it’s all downhill from here.

So, at 2,500 words, I will now take a break. Let’s leave Rover under new management but with a world-leading mid-sized saloon, a much-loved big saloon, a supercar and a ground breaking 4×4. Sadly, it’s all downhill from here.

It’s very telling that last year, when Renault severely pruned their UK car range the Espace and Laguna models were amongst the casualties. These ruled the family car roost in the early- to mid-90s but sales have dwindled. Equally telling is that one of Ford’s other actions on ‘Black Thursday’ was to push back the introduction of the next generation Mondeo to 2014 (even though the car has already been unveiled) and instead speed up plans to introduce the next-gen Mustang to Europe. It says a lot about the weirdness of the European car market that the solution to Ford’s problems is to stop work on a 3-box family saloon and instead bring in a high-performance sports coupe.

It’s very telling that last year, when Renault severely pruned their UK car range the Espace and Laguna models were amongst the casualties. These ruled the family car roost in the early- to mid-90s but sales have dwindled. Equally telling is that one of Ford’s other actions on ‘Black Thursday’ was to push back the introduction of the next generation Mondeo to 2014 (even though the car has already been unveiled) and instead speed up plans to introduce the next-gen Mustang to Europe. It says a lot about the weirdness of the European car market that the solution to Ford’s problems is to stop work on a 3-box family saloon and instead bring in a high-performance sports coupe.